Honoring heritage and reuniting families

Same Name, Wrong Ancestor: Why Verifying Family History is Critical for Tribal Enrollment

In genealogy, names can deceive. Just because someone shares the same name, hometown, or even birth year as your ancestor does not mean they are your ancestor. When it comes to tribal enrollment, especially in nations like the Cherokee Nation where proof of Dawes Roll ancestry is required, getting it wrong can mean denial of citizenship. This is exactly what happened in the case of Chris. He and several relatives believed they descended from a Willie Thompson listed on the Dawes Roll. Some of his cousins had even been accepted as Cherokee citizens. But when Chris applied, his application was denied. That denial prompted a closer look and what we uncovered offers an important lesson in genealogical accuracy.

Aimee Rose-Haynes

11/14/20255 min read

The Problem: Multiple Willie Thompsons in Indian Territory

Chris’s ancestor was named Willie Reburta Thompson, born in 1901 in Indian Territory. On the surface, this looked promising. The name Willie Thompson appears more than once on the Dawes Roll. So it seemed logical to assume she must be one of them.

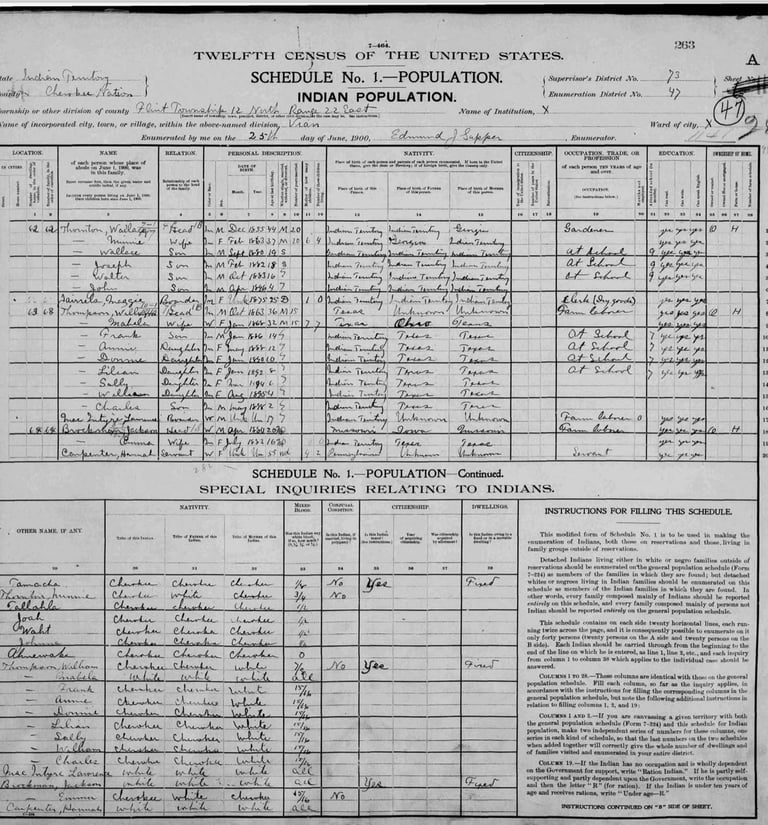

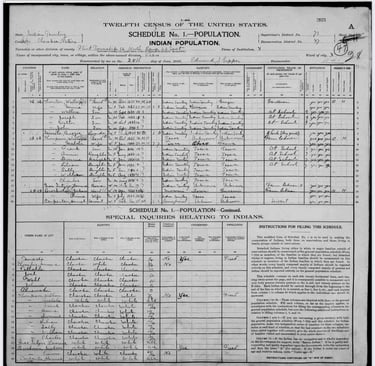

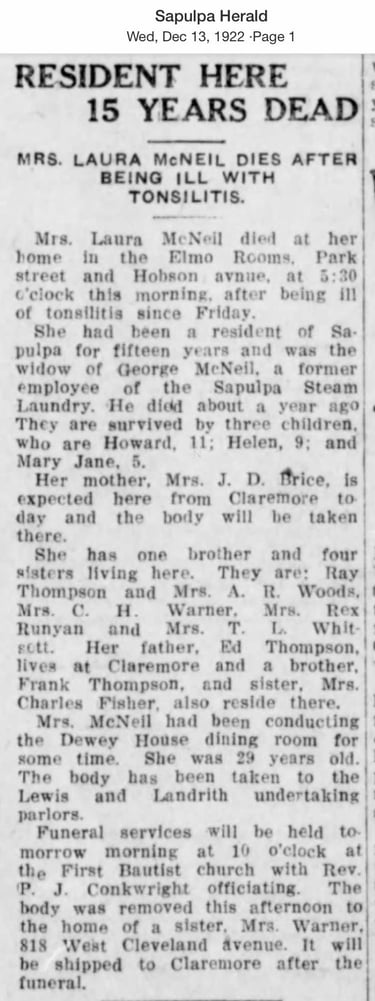

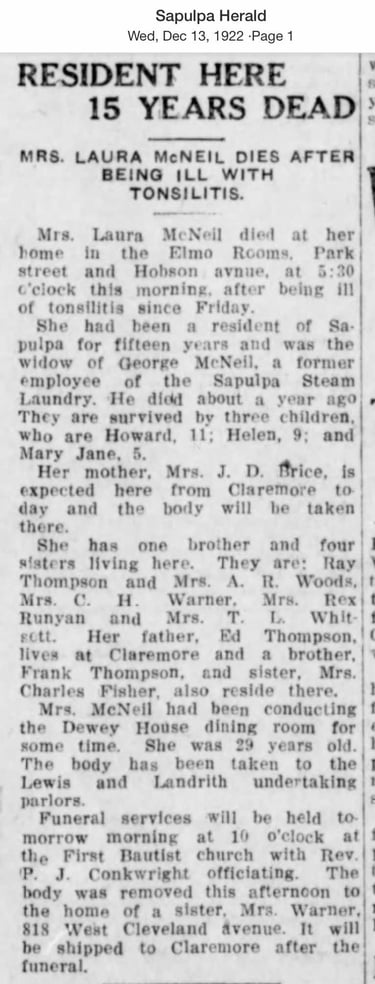

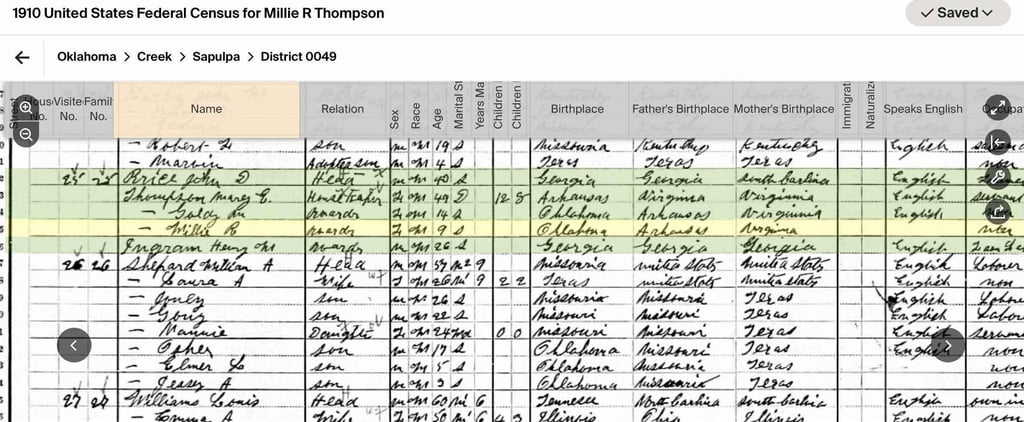

But once we started comparing the historical records, it became clear that there were three different individuals named Willie Thompson, all born in Indian Territory, all living around the same time, and all with the father of William Thompson.

To sort them out, we used Dawes enrollment records, census schedules, obituaries, and family structure comparisons.

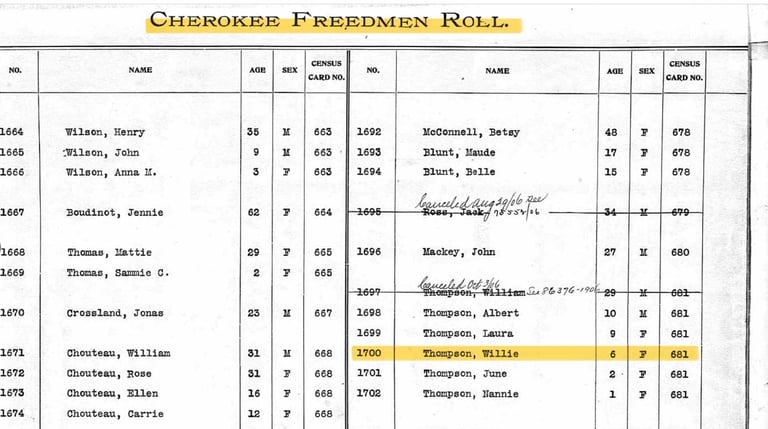

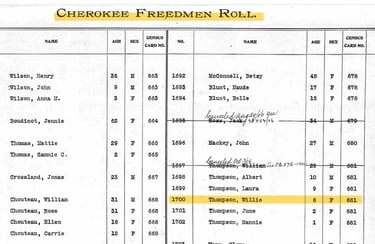

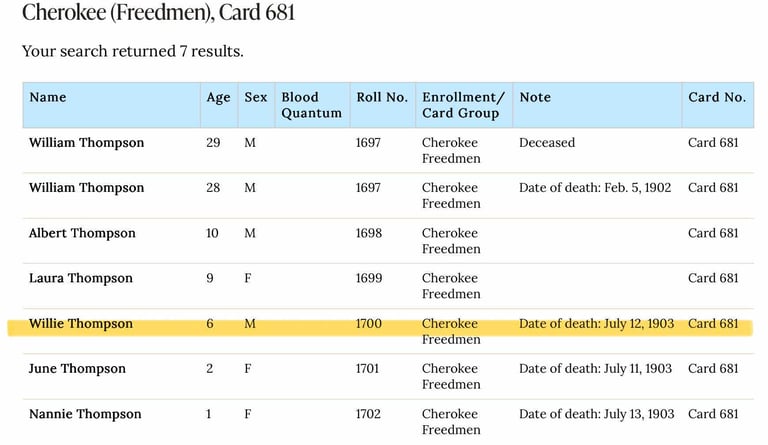

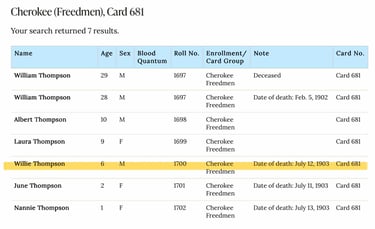

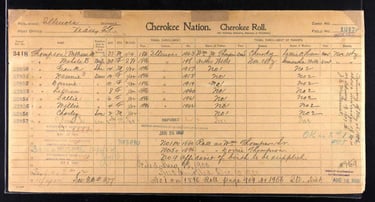

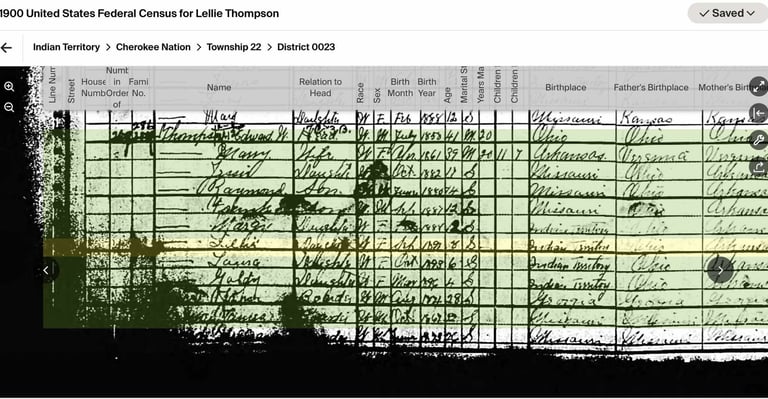

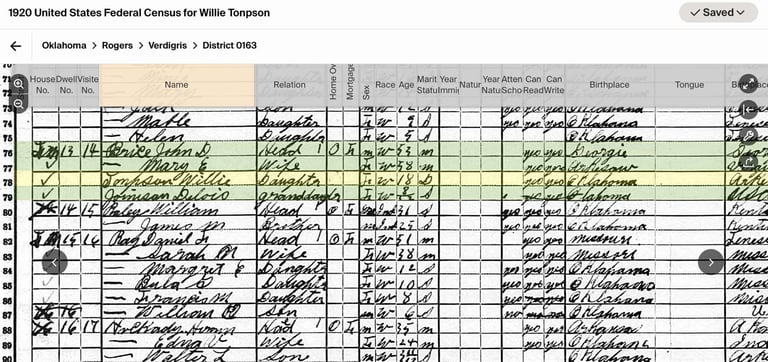

Candidate 1: Willie Thompson (Freedmen Card #681)

This Willie Thompson was listed as a 6-year-old female on Cherokee Freedmen Card 681.

- Belonged to a Freedmen family enrolled under William Thompson

- Died young on July 12, 1903, which ruled her out as a possible match

- Had siblings named Albert, Laura, June, and Nannie

Conclusion: Not Chris’s ancestor. This Willie passed away as a child and cannot be the same person who later married and had children. Willie is also on the Freemen Card meaning she was of African American ancestry.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

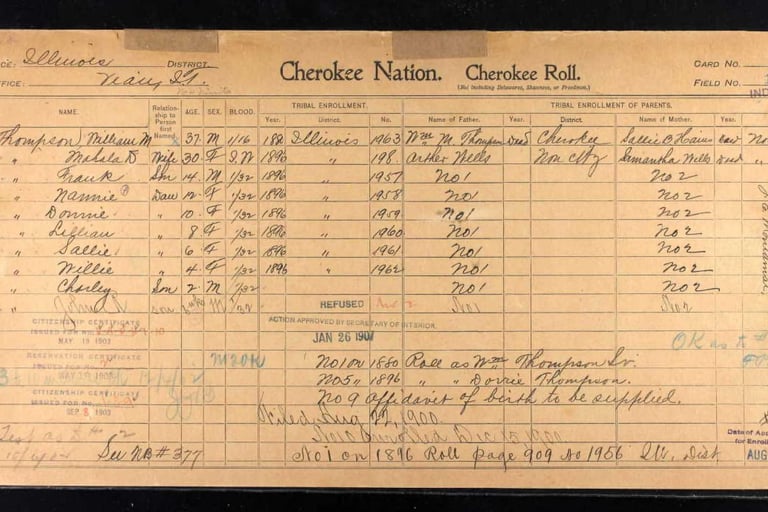

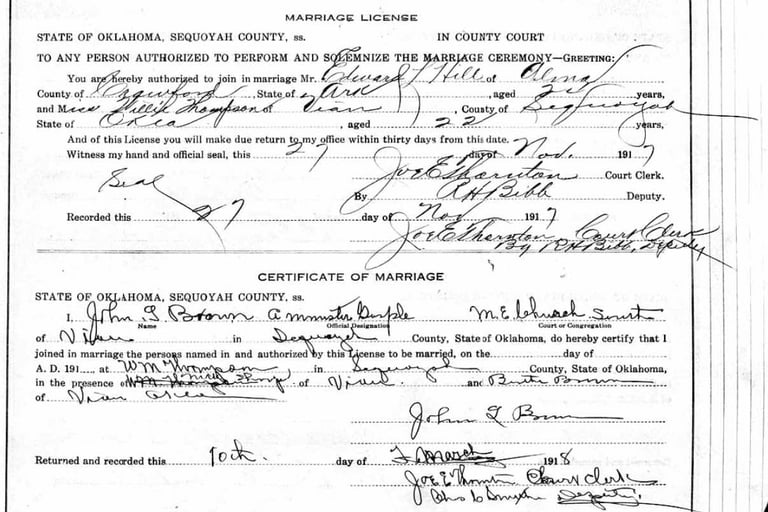

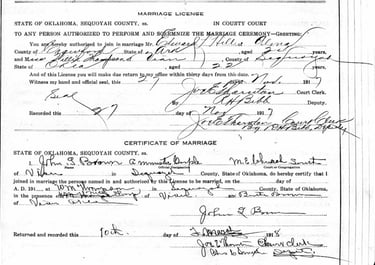

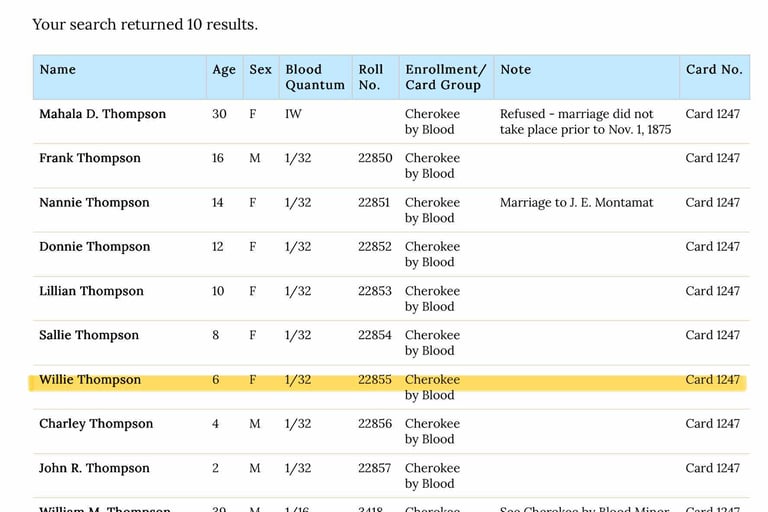

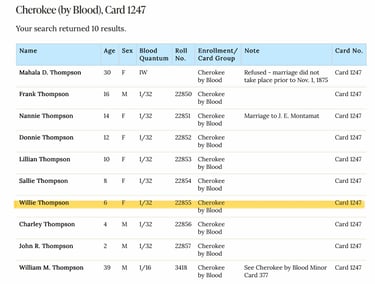

Candidate 2: Willie Thompson (Cherokee by Blood Card #1247)

This individual was a female enrolled on Cherokee by Blood Card #1247, listed as 6 years old.

- Daughter of William M. Thompson and Mahala D. Wells

- Willie is well documented including her marriage to Edward Lee Hill in 1917

- Willie died in 1995

- Lived in Vian, Oklahoma, where her family helped establish the town

Conclusion: Not the correct lineage. This is a separate family, unrelated to Chris.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

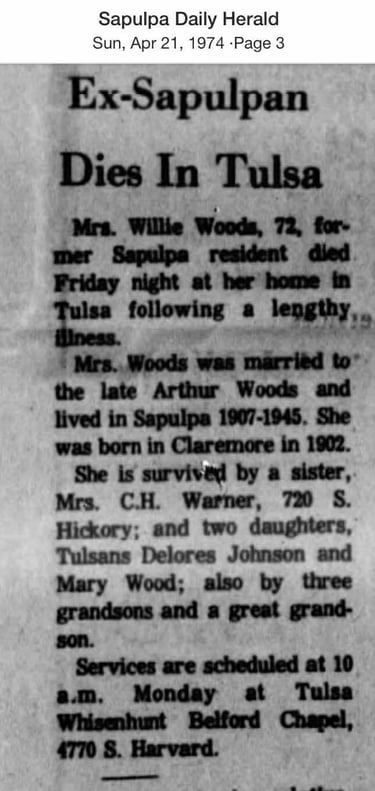

Candidate 3: Willie Reburta Thompson (Chris’s Ancestor)

Now let’s turn to the actual person in question, Chris's ancestor.

- Born May 28, 1901 in Indian Territory

- Parents: William Edward “Ed” Thompson and Mary E. Riggs

- Raised in Sapulpa and Claremore, Oklahoma

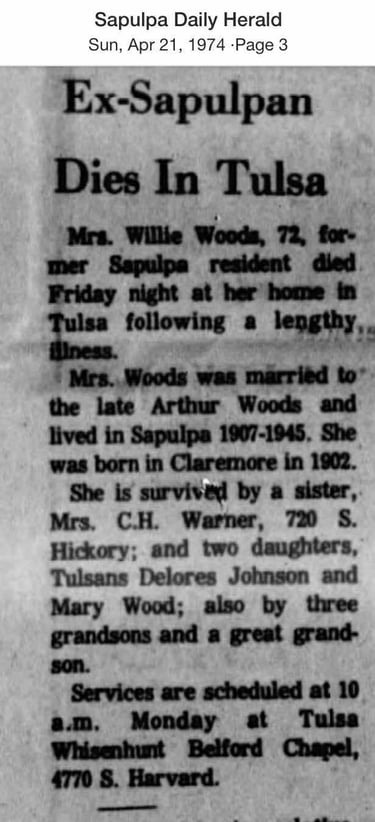

- Married Arthur Woods and raised a family

- Died April 19, 1974, in Tulsa

We verified her identity using a combination of records including census entries, obituaries, and family relationships. This Willie is the direct ancestor to Chris.

How to Avoid Mistaken Identity in Genealogy

Tips to Verify Your Research and Strengthen Your Family Tree

When researching your family history, it is easy to fall into common traps. Names repeat across generations and locations, stories get passed down without proof, and assumptions can replace documentation. But if your goal is accuracy, especially in cases involving tribal enrollment, citizenship, or legal documentation, getting it right matters.

Here are some practical tips to help you verify your information and become a more effective researcher.

1. Same Name Does Not Mean Same Person

Just because someone shares your ancestor’s name does not mean they are the same individual. This is especially true for common names like John Smith, Mary Johnson, or in our case, Willie Thompson.

What to do:

Compare full names, middle initials, and nicknames.

Verify birth and death dates, spouses, and children's names. Make sure these match the records for the individual you're researching. Example with Willie, she was married to Arthur Wood yet the Dawes Willie was married to Edward Hill

Check for duplicate names in the same area and eliminate those who do not match.

2. Use Multiple Records to Confirm Identity

One record is never enough. Every relationship, date, or identity in your tree should be backed by at least two or three reliable sources.

What to do:

Pair census records with birth, marriage, and death certificates.

Use wills, land records, or obituaries to fill in the gaps.

Seek consistency across documents before adding someone to your tree.

3. Check Siblings, Parents, Locations, and Life Events

The best way to confirm you have the right person is by looking at the whole family unit. A single individual is harder to trace than an entire household.

What to do:

Research siblings and cousins to build out the full family group.

Look at marriage, baptism, or probate records that list multiple family members.

Make sure their movements and life events line up chronologically and geographically.

4. Do Not Rely on Family Stories Alone

Oral traditions are valuable, but they are not proof. Family legends can point you in the right direction, but you must back them up with records.

What to do:

Treat family stories as clues, not confirmations.

Search for documentation that supports or contradicts the tale.

Be open to adjusting your understanding based on new evidence.

5. Keep Detailed Source Citations

Documentation is key to building a credible tree. If you cannot explain where a fact came from, you cannot defend it later.

What to do:

Record full source information for every fact in your tree.

Note whether it is a primary or secondary source.

Revisit sources periodically to ensure they still support your conclusions.

6. Use DNA Testing to Support Your Research

Genetic genealogy can help confirm biological relationships when paper trails fall short.

What to do:

Test yourself or older relatives who are one generation closer to the line in question.

Use shared match tools and chromosome browsers where available.

Combine DNA evidence with documented records for stronger results.

This tip does not help with proving Native American ancestry in itself, always follow your paper trail to verify.

7. Revisit Old Records with Fresh Eyes

Early research may contain errors made from inexperience or lack of information. Re-examining that research with more knowledge can lead to major breakthroughs.

What to do:

Go back to early ancestors in your tree and verify each fact.

Look for outdated sources or unproven assumptions.

Use new tools and databases that were not available when you first researched.

8. Use Timelines to Catch Contradictions

Timelines help you visualize a person’s life and quickly spot inconsistencies.

What to do:

Build a timeline of major life events including births, marriages, moves, and deaths.

Watch for overlapping dates or improbable gaps.

Compare your timeline to known historical events or migration patterns.

Final Thoughts

Being a good family historian means being a careful one. Accuracy should always take priority over convenience. Whether you are building your first tree or revisiting old research, these habits will help you avoid the same-name trap and ensure your work holds up for generations to come.

If you are dealing with a confusing ancestor or trying to confirm tribal lineage, take your time, use your tools, and remember that every detail counts.