Honoring heritage and reuniting families

The Dakota War 1862

This year marks 163 years since the Dakota War of 1862, a six-week conflict that forever changed the history of Minnesota and the Dakota people. Often called one of the darkest chapters in the state’s past, it was born out of broken treaties, starvation, and desperation. What began with four young Dakota men near Acton, Minnesota, quickly spiraled into a violent struggle that claimed hundreds of lives, displaced thousands, and led to the largest mass execution in U.S. history. Understanding what happened in 1862 is not just about remembering tragedy… it is about acknowledging resilience, injustice, and the echoes of history that still shape communities today.

-Aimee Rose-Haynes

9/24/20254 min read

The Dakota War of 1862: A History of Land, Starvation, and Struggle

This year marks 163 years since the Dakota War of 1862, a conflict that forever altered Minnesota and the Dakota people. To understand the war, we must first acknowledge that the region now called Minnesota is the homeland of the Dakota. The very word “Minnesota” comes from the Dakota phrase Mni Sota, meaning “Land Where the Water Reflects the Clouds.” The confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers, known as Bdote, is a sacred place for the Dakota. It is considered their place of creation, where they came into being as the Wicahpi Oyate, the Star Nation.

Broken Treaties and Rising Tensions

The seeds of the U.S. Dakota War were sown decades before the first shots were fired. In 1805, Lt. Zebulon Pike negotiated a treaty with only two of seven Dakota leaders present at Bdote. The agreement gave the United States 100,000 acres of land for the construction of a fort and trade posts. Though the land was valued at $200,000, the Senate later approved payment of just $2,000. It was the first of many fraudulent treaties the Dakota would endure.

In 1851, the Treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota forced the Dakota to give up 24 million acres of land in exchange for promises of $3.75 million in annuities. Much of the promised money went directly to fur traders to cover alleged debts. The Dakota were pushed onto a narrow reservation along the Minnesota River and pressured to abandon their way of life. They were told to cut their hair, adopt Christianity, till the soil, and give up hunting. Many resisted, while others tried to adapt, creating deep divisions within Dakota society.

As Minnesota became a state in 1858, settlers poured into the territory. The Dakota were forced to cede even more land. Logging, farming, and expansion destroyed prairies and forests, disrupting the Dakota’s seasonal cycles of hunting, fishing, and gathering wild rice. Starvation became a constant threat.

Hunger, Desperation, and Outbreak of War

By 1861, crop failures, a harsh winter, and the near extinction of game left the Dakota in crisis. When payments and food supplies from the government were delayed, traders refused to extend credit. Andrew Myrick, a trader at the Lower Sioux Agency, infamously declared, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass or their own dung.”

On August 17, 1862, four young Dakota men killed five settlers near Acton after a dispute. That night, leaders met in council. Some urged peace, but Chief Little Crow reluctantly agreed to lead an attack, saying war was the only option left. At dawn on August 18, Dakota warriors attacked the Lower Sioux Agency, killing traders and settlers, including Myrick, whose body was later found with grass stuffed in his mouth.

The war spread quickly. Dakota forces struck settlements across southern Minnesota, attacked New Ulm twice, and laid siege to Fort Ridgely. More than 500 settlers were killed, and thousands fled. At the same time, many Dakota opposed the fighting, protecting neighbors or helping free captives.

The U.S. Military Response

Colonel Henry Sibley, a former governor, led hastily assembled militias and volunteer soldiers. The conflict reached its climax on September 23, 1862, at the Battle of Wood Lake, where U.S. forces defeated Little Crow’s warriors. Days later, 269 captives, mostly women and children, were released at Camp Release. Nearly 2,000 Dakota, including many who had opposed the war, surrendered or were taken into custody.

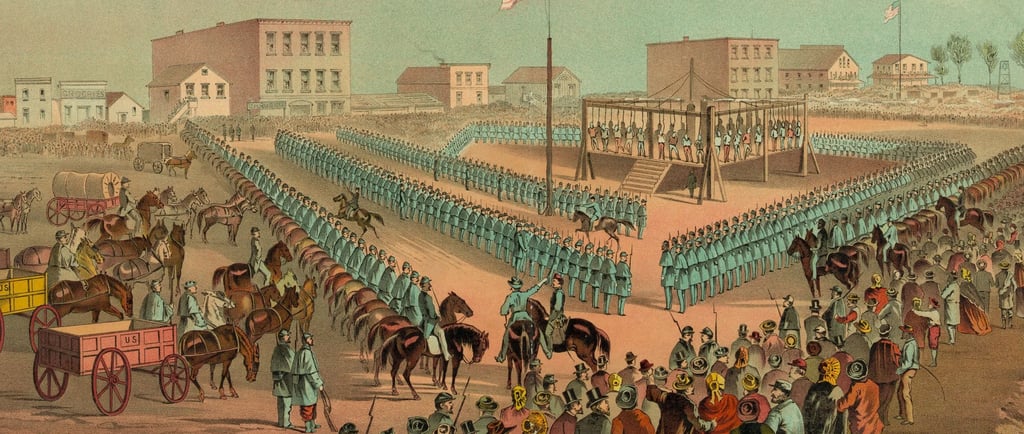

Trials, Executions, and Exile

In the war’s aftermath, military tribunals sentenced 303 Dakota men to death after brief trials that lacked due process. President Abraham Lincoln reviewed the cases and commuted most sentences, but approved 39 executions. On December 26, 1862, 38 Dakota men were hanged in Mankato, Minnesota, in the largest mass execution in U.S. history.

Survivors faced even more suffering. About 1,600 Dakota, mostly women, children, and elders, were forced into an internment camp below Fort Snelling. Poor conditions led to hundreds of deaths from disease and starvation. In 1863, Congress annulled all Dakota treaties, abolished their reservations, and ordered their permanent removal from Minnesota. Survivors were sent to Crow Creek in present-day South Dakota, where many more died. The Ho-Chunk people, who had not been involved in the conflict, were also expelled.

Legacy and Memory

For generations, Minnesota settlers remembered the war through stories of pioneer loss, while Dakota families carried the grief of exile, execution, and broken promises. Little Crow himself was killed in 1863 near Hutchinson, Minnesota, his scalp displayed and his remains desecrated before being returned to his family over a century later.

In recent years, Minnesota has begun to face this painful past. In 2012 and 2013, Governor Mark Dayton repudiated Governor Alexander Ramsey’s 1862 call to “exterminate” or drive out the Dakota. In 2019, Governor Tim Walz issued a formal apology for more than 150 years of trauma inflicted by state government. In 2021, land near the Lower Sioux Agency battlefield was returned to the Dakota people, a symbolic act of justice long overdue.

A Tragic but Enduring History

The Dakota War of 1862 was more than a six-week conflict. It was the culmination of decades of broken treaties, exploitation, and cultural suppression. The war and its aftermath remain among the darkest episodes in Minnesota’s history, but also a testament to the Dakota people’s survival.

As Lower Sioux President Robert Larsen said when land was finally returned, “Our ancestors paid for this land over and over with their blood, with their lives. It’s not a sale; it’s been paid for by the ones that aren’t here anymore.”

One hundred and sixty-three years later, the story of the Dakota War reminds us of the devastating costs of injustice and the importance of truth, reconciliation, and remembrance.