Honoring heritage and reuniting families

Ohio’s (Surprisingly Peaceful) Witch Trial: Nancy Evans of Bethel, 1805

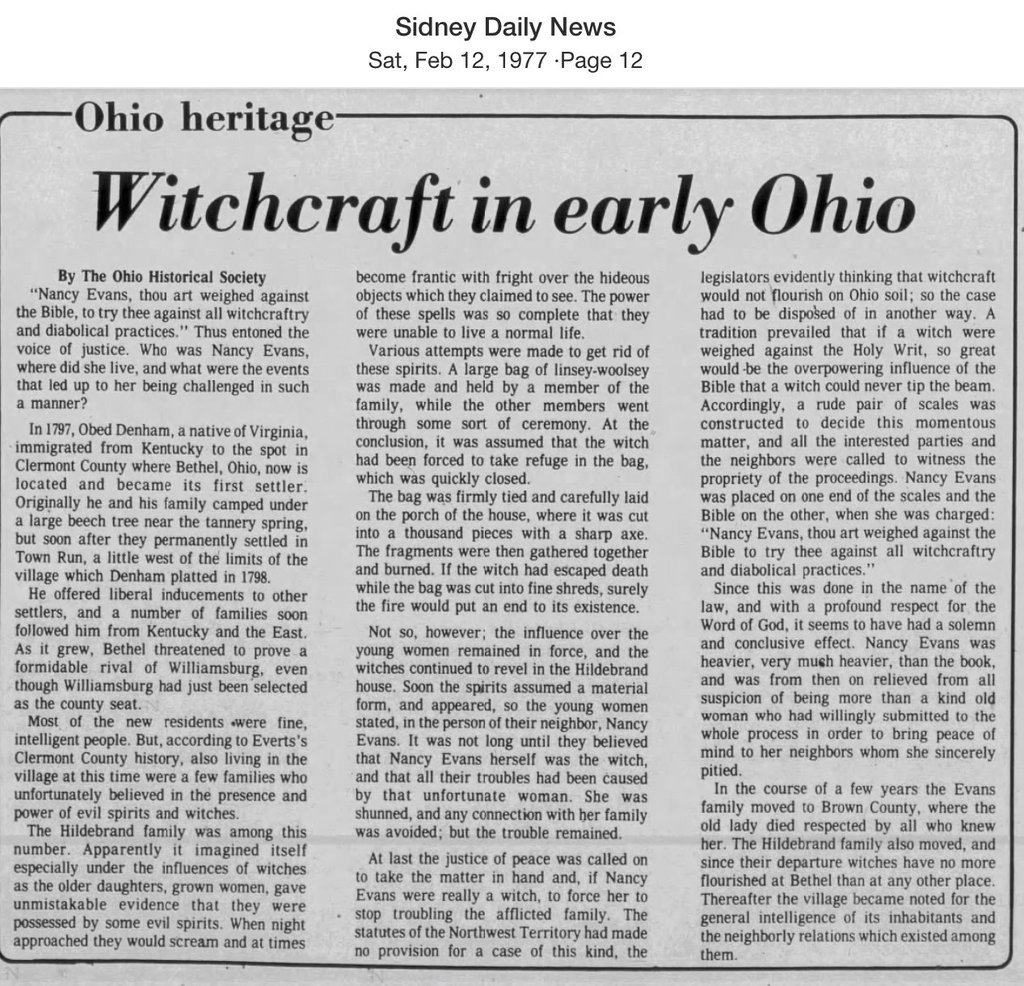

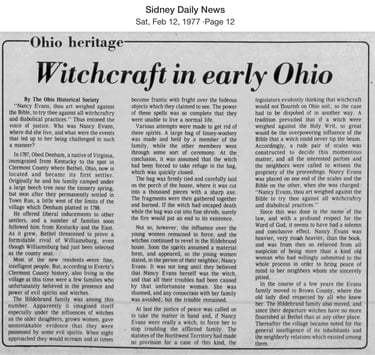

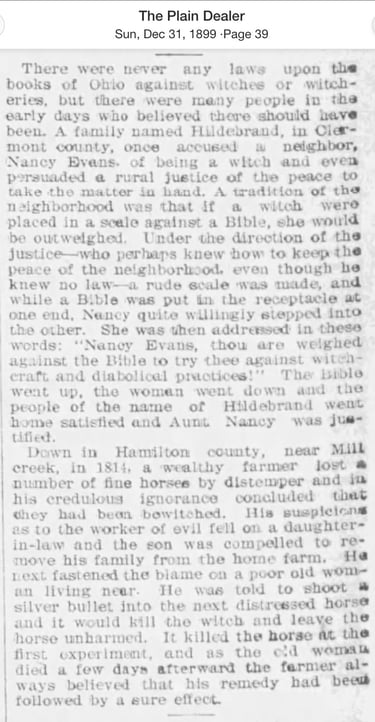

When we think of witch trials, our minds leap immediately to Salem, Massachusetts in 1692, where accusations of witchcraft ended with the deaths of twenty innocent people. By the early 1800s, Americans often viewed those events as a dark cautionary tale from the past. Yet, remarkably, superstition lingered long into the young republic. In 1805, in the frontier town of Bethel, Ohio, a local woman named Nancy Evans stood accused of witchcraft. Her trial was the only one of its kind in Ohio’s history. And while it followed familiar patterns of fear and accusation, its conclusion was very different. No gallows, no drowning, no burning. Instead, the people of Bethel staged a strange ritual, proclaimed her innocent, and quietly moved on.

-Aimee Rose-Haynes

10/11/20254 min read

Frontier Ohio in 1805

When Ohio became a state in 1803, it was still a wild frontier. Clermont County, where Bethel was located, was a patchwork of new farms carved out of dense forests. The settlement itself had been founded just a few years earlier by Obed Denham and was home to farmers, millers, and craftsmen.

Life was precarious. Illness swept through cabins without warning, crops failed, and communities were isolated. People leaned heavily on their faith for guidance, but they also carried old folk traditions from Europe and colonial America. In that mix of religion and superstition, unusual events could quickly take on sinister meaning.

Nancy Evans: The Accused

Very little is known about Nancy Evans before the trial. Accounts describe her as an elderly widow who lived alone in a small cottage at a crossroads. She owned a black cat, and in the eyes of some neighbors, that was enough to mark her as different.

Her nearest neighbors were the Hildebrand family, and it was within their home that suspicion first arose. Two of the Hildebrand daughters began experiencing fits and strange behavior. In a time before epilepsy, mental illness, or stress were well understood, these symptoms were often attributed to supernatural forces. The daughters insisted that Nancy Evans and her cat were tormenting them, claiming the animal could even speak and assault their minds.

The Hildebrands believed them. Soon, the family and their neighbors began to shun Nancy Evans. The Hildebrands called the justice of the peace with the witch allegations.

A Magistrate Steps In

The growing tension reached a point where local officials had to get involved. But here was the problem: Ohio, unlike colonial Massachusetts, had no laws against witchcraft. This was early into Ohio's newly establish statehood. By the 19th century, such laws were considered relics of an unenlightened past. Still, the community wanted action, and ignoring the accusations risked unrest.

The magistrate in Bethel devised a compromise. He ordered a device built known as the “witch’s chair.” This test, adapted from old European and colonial practices, would allow the community to settle the matter publicly without resorting to violence.

The Witch’s Chair: Two Versions

Accounts of the Bethel trial vary, and two versions of the “witch’s chair” have come down through history:

The Water Test: A long pole was suspended over a body of water with a swing on the end. The accused sat on the swing, while a Bible was placed on the other side of a balance. If the accused weighed less than the Bible, they were declared a witch and could be dumped into the water. This “test” was deadly, since most women could not swim, and heavy clothing like corsets, petticoats, and boots dragged them under.

The Scale Test: A set of large, human-sized scales were built. A Bible was placed on one side, and the accused sat on the other. If the accused outweighed the book, they were proclaimed innocent.

Some versions of the Nancy Evans story reference water, but most agree it was the second version that was used in Bethel.

The Trial of Nancy Evans

When the day of the trial arrived, the townspeople gathered at what is now the intersection of State Routes 125 and 232. A heavy Bible was placed on one side of the scale, and Nancy Evans was seated on the other.

Nancy, who thought the whole proceeding was absurd, reportedly sat down heavily on the chair. She was not a small woman, and the Bible shot upward as the scale tipped decisively in her favor.

The magistrate announced that the Word of God had not been bested, and the crowd, perhaps embarrassed but also relieved, accepted the verdict. Nancy Evans was acquitted then and there.

The Aftermath

Although Nancy’s name had been cleared, the ordeal left scars. In a small community, suspicion does not vanish easily. Nancy Evans eventually moved to Brown County where she passed quietly and was respected by her new community, while the Hildebrands also left Bethel. Both families had been tainted by the trial, one as accused and the other as accusers. It

The case ended quietly, with no executions or imprisonments, but it reshaped the social fabric of Bethel.

Why This Case Still Matters

The Hildebrand-Evans witch trial remains the only recorded witchcraft trial in Ohio. It reminds us that fear and superstition lingered long after Salem and that even in a young state shaped by democratic ideals, frontier communities could still fall back on folklore when faced with the unknown.

It is also significant because it shows restraint. The community created a ritual to relieve its fears without destroying a life. Nancy Evans walked away humiliated but alive, and history records the trial as a curiosity rather than a tragedy.

Today, the story is told in Clermont County as a unique local legend. At the crossroads where the trial took place, the lesson lingers: fear can divide neighbors, but sometimes reason, humor, and even a bit of common sense can keep hysteria from becoming deadly.