Honoring heritage and reuniting families

Kill the Indian, Save the Man: History of Indian Schools

They were taken from their homes, their hair cut, their names erased, and their languages silenced. To many, the buildings looked like schools, but inside was a system designed to break spirits and erase identities. Native children, some as young as five, were forced into a world where everything they knew was called wrong, savage, or shameful. This is not just a chapter in history. It is a story of stolen childhoods, generational pain, and enduring strength. Before the first lesson was ever taught, the goal was clear: to kill the culture and save the man.

Aimee Rose-Haynes

8/13/20254 min read

Indian Schools and the War on Indian Culture

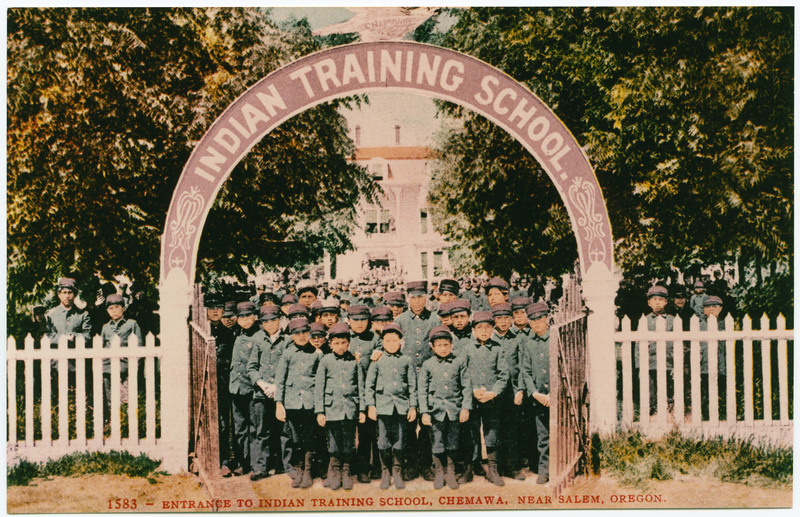

In the late 1800s, as the battles between Native tribes and the U.S. military drew to a close, a different kind of war began. This war was not waged with rifles and swords. It was fought in classrooms, with chalkboards, abuse, forced rules, and murder. It was a war aimed at the very heart of Native identity. At the center of this campaign were the Indian boarding schools, institutions created with one mission: to strip Native children of their culture, language, and traditions and replace them with Euro-American values.

These schools were not about opportunity. They were not places where children could thrive or play. They were tools of assimilation, designed to reshape the identities of Native youth and turn them into something the government considered acceptable. This was not education through empowerment. It was erasure through control.

One of the most vocal advocates for this system was Richard Henry Pratt, a former military officer and founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. He summed up the entire philosophy with a chilling phrase: "Kill the Indian in him and save the man." This was the goal behind every lesson, every punishment, and every policy.

By 1877, Congress began funding Indian education, believing it was a cheaper alternative to warfare. One congressman even stated that it cost less to educate Native people than to kill them. On the surface, it may have sounded like progress. But beneath that justification was a deeply harmful agenda.

Children were taken from their homes, some through persuasion and others by force. At the Mescalero Apache Agency in Arizona, an agent reported in 1886 that police had to raid camps without warning, seizing children and taking them to school against their families' wishes. Some parents hid their children in the hills or sent them to relatives far away. But the officers came anyway. The agent described the children being chased and captured like wild animals. Parents were left heartbroken and powerless. The children were frightened, confused, and stripped of any sense of safety.

Once at school, the transformation began immediately. The children were stripped of their traditional clothing. Their belongings were taken. Their long hair was cut short and often treated with kerosene to kill lice. They were issued uncomfortable uniforms and stiff leather shoes. Boys were taught trades like carpentry or farming. Girls were trained in cooking, sewing, and housework. The purpose was not to prepare them for independent lives, but to mold them into servants of white society.

The most devastating change was the loss of identity. Native names were erased. Children were often given English names from a list written on a chalkboard. As Luther Standing Bear remembered, this moment was deeply painful. His Lakota name, filled with meaning and tied to his ancestors, was replaced in seconds. If the children refused to use their new name, they were beaten or starved until they complied.

One of the most well-known schools was the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, which opened in 1879. It became the model for other institutions across the country. Carlisle introduced the "outing system," which placed Native children in white households during school breaks. The goal was to immerse them in white culture and sever their connection to tribal life. The school’s motto reflected this mindset: "To civilize the Indian, get him into civilization. To keep him civilized, let him stay."

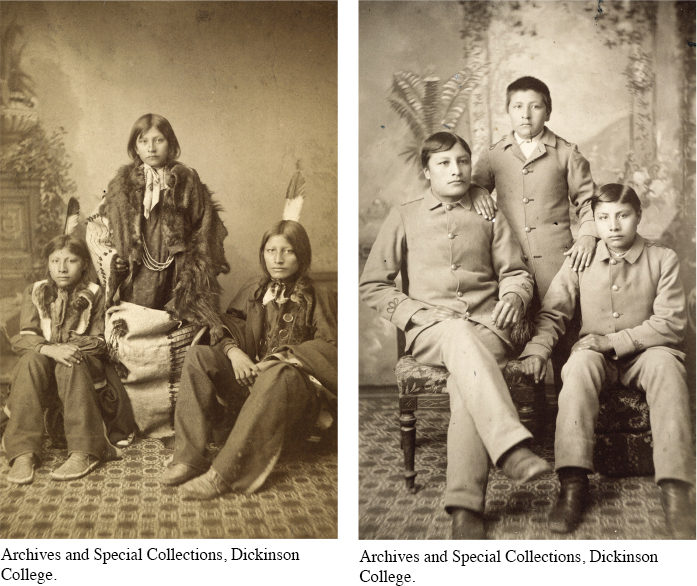

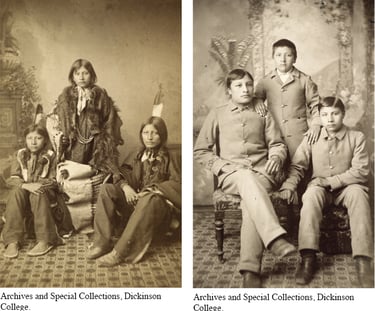

Sioux students before and after photographs featuring Wounded Yellow Robe, Timber Yellow Robe, and Henry Standing Bear illustrates the dramatic shift away from their tribal identity following their enrollment at Carlisle Indian School in 1883. Schools like Carlisle were part of a broader federal policy aimed at erasing Native culture and reshaping Indigenous youth into the mold of Euro-American society.

These schools were not only about language and clothing. They were tied to the economic values of the time. Merrill Gates, a government official, once described the purpose of Indian education as getting the Indian out of the blanket and into trousers, trousers with a pocket that aches to be filled with dollars. This statement captured the materialism behind the mission. Native values of sharing, community, and spiritual connection were seen as obstacles to progress.

Despite all this, Native children resisted. They whispered in their tribal languages when the teachers were not looking. They sang songs quietly at night. They clung to their stories and honored the teachings of their elders. Zitkala-Sa, a Yankton Dakota woman who attended boarding school, later wrote about the loneliness and pain, but also about the courage of those who refused to forget who they were.

Even those who tried to follow the rules held onto their roots. Luther Standing Bear, who attended Carlisle, later wrote that he wore the uniform, but he never truly left behind the blanket. The schools had hoped to erase Native identity, but often ended up creating something unexpected. They brought children from many different tribes together. These students, despite the abuse they endured, developed a shared language and experience. That common ground later became the foundation for a pan-Indian movement in the early 1900s. Former students used their voices to speak out against injustice and demand better treatment for their people.

The legacy of these schools is painful. Many children died in those institutions. Some were buried in unmarked graves far from home. Others returned to their families but felt like strangers, caught between two worlds. Generations of Native communities carry the wounds left behind by this system.

But the story does not end in silence. Across the United States and Canada, tribes are now working to reclaim their languages, revive their traditions, and tell the truth about what happened in those schools. Survivors have shared their stories. Communities have held ceremonies to honor those who never came home. Some schools have been turned into museums, so that the lessons of the past are never forgotten.

The Indian boarding school system tried to erase a culture and its people, but it failed. Native nations are still here. They are singing, dancing, speaking, teaching, and healing. What was meant to be the end of Native culture has instead become a powerful story of survival.

Pacific University Archives